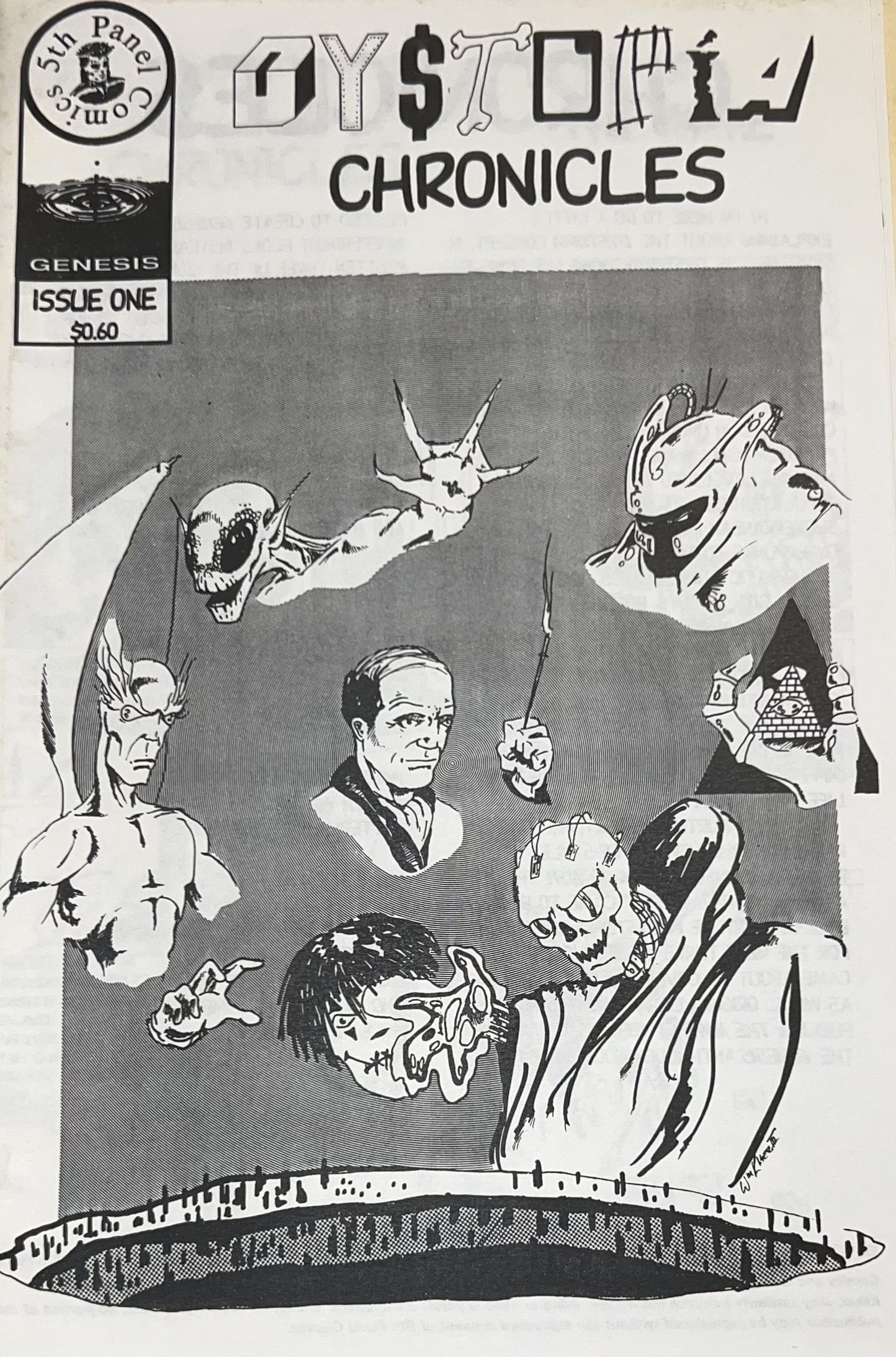

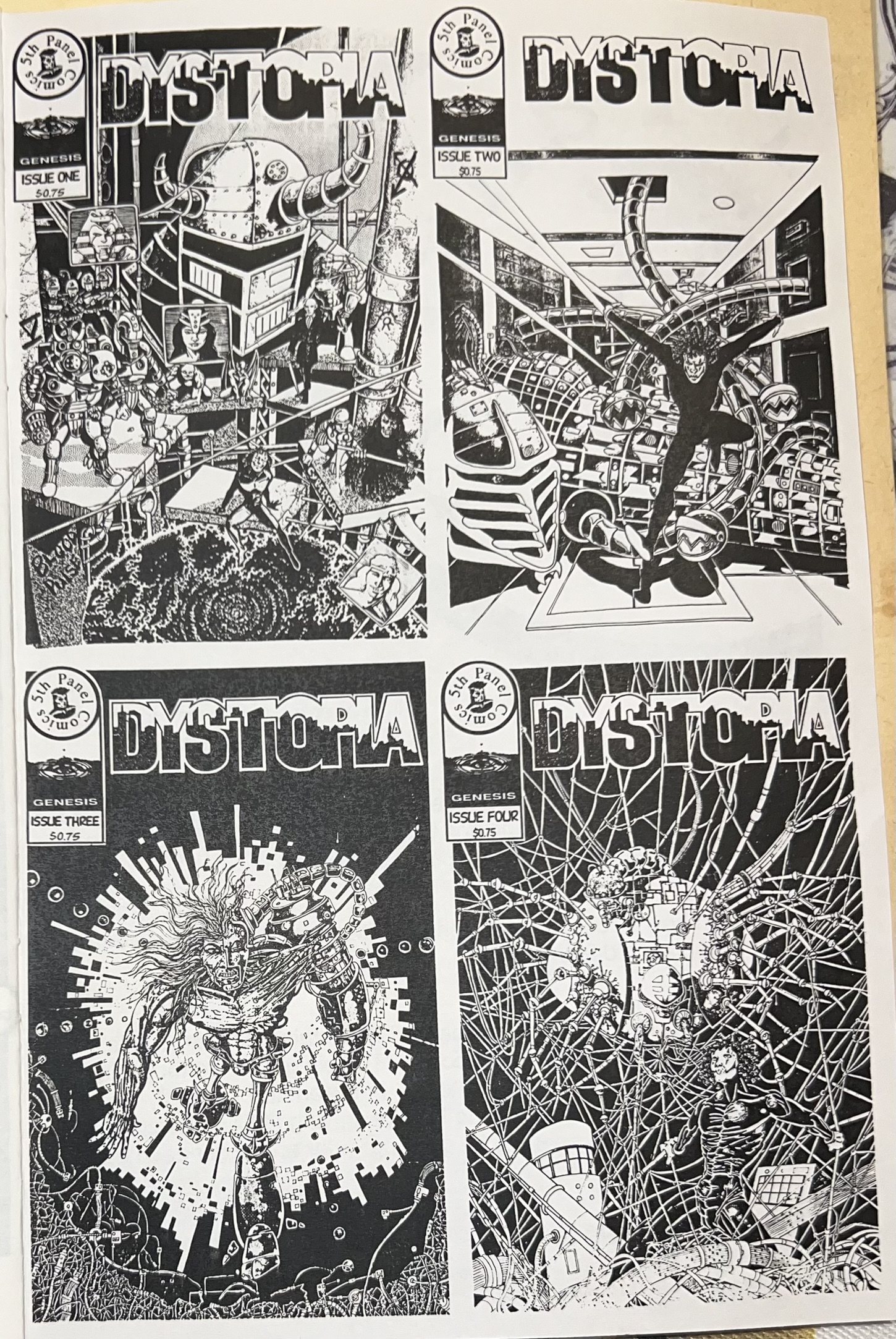

Me being me and having new stories and characters springing into my head on an hourly basis, I immediately knew that just doing one book and calling it “Dystopia” wasn’t going to serve the situation. With a setting that was already crossing genres, I figured there had to be some kind of general direction for the stories we would all be telling but it was hard to contain them in just one anthology title. So, instead of one book, I imagined three: Dystopia: Chronicles, Dystopia: Gangwars, and Dystopia: Shadows on the ‘Net.

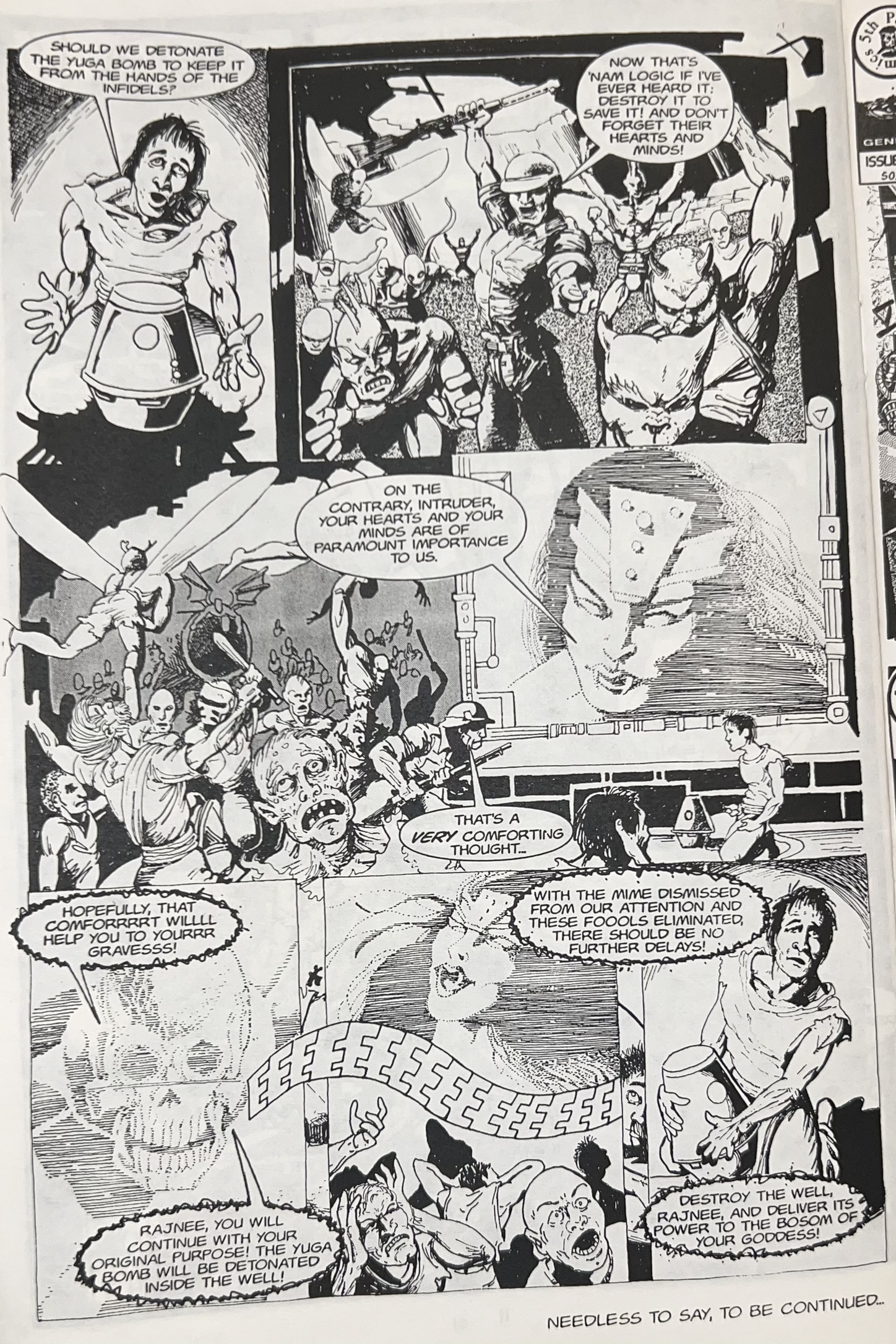

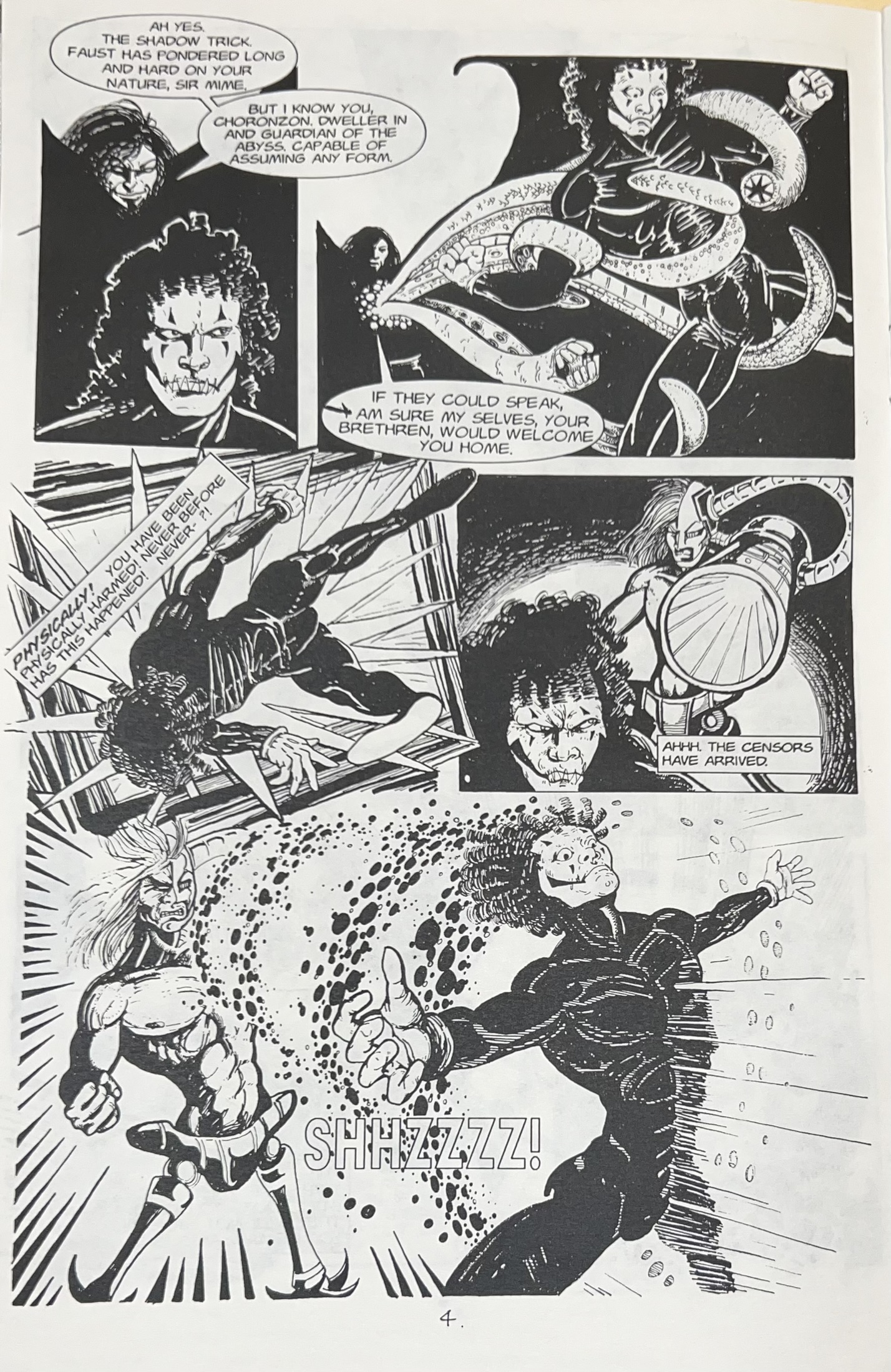

None of them were specifically tied to any one topic or area of interest, but Chronicles was intended to be more of the “general purpose” book. If anyone had a story that wasn’t centered around one of the gangs or action taking place on the ShadowNet, then it would probably be a Chronicles story. The first effort that Will and I made specifically targeted for the setting was one that involved The Mime, The Iron Wizards, and two of the lesser-known gangs on Eight: The Trolldiers and The Firewalkers. The main character for the tale was The Mime, who was a concept that I’d jotted down in the fabled notebook a while before Dystopia occurred to me. I wanted to try to tell a story that was a second-person perspective, in that the narrator wasn’t internal (first-person) or talking about the lead character (third-person) but was instead talking to them, such that all of the captions are as if I was personally responding to what was happening, as would normally be the case in first-person, exccept that The Mime, of course, doesn’t talk. So most of the “internal” dialogue was me, as the narrator, saying things to The Mime: “You know that this is happening because of who you are. You can’t allow it to proceed.” And so on. I thought it would be an interesting exercise and the character presents a good example of how there are very few “good guys” in the setting and what the internal thoughts of a “non-good guy” might be, since we so rarely were presented with that approach in fiction of the time (It’s much more common now; see Breaking Bad, etc.) Even the nominal “heroes” are just lighter shades of gray than the nominal “bad guys”, which is a lot closer to real life than the typical white hats/black hats approach that tends to dominate that superhero/adventure/horror story scene.

The “badder” guys in this case would be the Iron Wizards. The name is something that other people have used for various video games and TTRPGs that have robots and/or modern technology showing up in fantasy worlds. As the famous Arthur C. Clarke quote goes: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” (Case example.) I wanted Corporate City, the third level, to be high-tech as a matter of course. All of those companies were staying in the Pit because of the tech that they were able to glean from sources like the Tech Walkers or that they were able to develop themselves and didn’t want to abandon. But the Wizards would be a step above even that. That’s also why I named them all after classic magicians from history and literature (Faust, Crowley, Wen Pa-Yang, Cagliostro, and Plotinus) as kind of a double entendre to their own name. But beyond even that, the name “Iron Wizards” isn’t something they call themselves. Internally, they refer to themselves as “The Pentacle”, while the Wizards tag is something that’s been placed on them by the surronding community, almost like an epithet, but also because it’s more of a street name than anything that seems vaguely elegant like they’ve selected.

That “street” perspective was important for Gangwars because one of the dominant forces throughout the city would be the gangs that inhabit every level, in one fashion and to one degree or another. It’s no secret that humans tend to factionalize into groups that share either one’s identity or one’s outlook on life, if not both. The most relevant example in the modern era of the latter is political parties, which have often been simply well-connected (and well-funded) gangs that happen to inhabit conference rooms, rather than neighborhoods (and sometimes both!) But, as a long-time RPG player, I was also familiar with settings where people clustering around different identities often went beyond racial underpinnings and into perspectives that drove them to a purpose (my favorite was Gamma World.) It was that context that pushed me to create most of the gangs (and more than one viewing of Walter Hill’s The Warriors, as a kid.) A few of them are central aspects of major parts of the setting, like The Phalanx. A few of them are simply tied to the genre setting of their associated level, like Canis Majoris. And a few are just concepts that wandered into the notebook and I figured I’d use because it seemed like a good idea at the time, like the Posh Street Flaming Screamers. Almost everyone whom I’ve ever given a copy of the bible to has stated that the gangs are among their favorite aspects to the whole picture.

The opening story of Gangwars was going to be an examination of daily life on the sixth level, The War Zone, and the direct conflict between The Phalanx and Bloodpulse as the two most powerful gangs on that, the most war-ravaged of any of the levels of the city, as the name implies. I wanted it to be an example of not only how different groups of people can factionalize, but how even within those factions, there are often radical differences of how to proceed. The central argument between High Chief Gall and Mad Stallion about how to deal with the immediate crisis, plus the growing threat to the immaculately neutral Pit Crew (the remnants of the International Red Cross who remained in the city) seemed to be a great way to show varying perspectives on the central conflict that dominates a good portion of the setting as a whole. It also touches on the importance of The Phalanx and the presence of the Tech Walkers as a regular threat to life and limb and a lot more of the larger turmoil in the city, which is usually driven by the most petty of goals; yards of territory, akin to the Western Front of World War I. Most of Gangwars would be taking place in “the real”, as opposed to “the now” of the third book.

Shadows on the ‘Net was intimately connected to one of the main aspects of the setting as a whole: The ShadowNet, which is the city’s main network. In the early 90s, it was my version of William Gibson’s “cyberspace”, but which had connections beyond just the databases created by massive computers (and, of course, his also did in his first novel, Neuromancer.) The ShadowNet is, in many ways, what drives the city as the isolated enclave of technology, magic, and other strange forces in near-future America, Inc. There’s a connection to The Well, the deepest level of the city. The Black Market on Five only exists because of the presence of the ‘Net. Just like what the Internet would become for us in the real world, the ShadowNet enables the commerce, communication, and primary interaction of the entire community. You don’t have to be connected to the ‘Net to survive in Dystopia, but it’s a lot easier if you know your way around it. If it’s not obvious, I was completely enamored with Gibson’s work, which is why Dystopia still carries a lot of that “old school cyberpunk” influence. Having been on the early versions of the Internet since 1984, I knew that this was going to be at the forefront of science fiction writing for the foreseeable future, even if I didn’t imagine just how dominant it would later become in the real world so quickly. (Neither did Gibson, really, as one of the more notable technologically awkward moments in Neuromancer is how its characters are still using pay phones to communicate…)

Despite it being the “third” book, I probably wrote more script for Shadows than I did for either of the other stories, even if none of it ever got to the point of being drawn. The initial story was one that involved the Morgue Lords, the Hanged Man, the gang, Control/Alt/Delete, the corporation, Metascience, and the crimelord, Macabre. It was a bit more wide-ranging than the other two and that probably played into my thinking becoming ”bigger” in some ways with another story rooted in the ‘Net that grew into its own thing entirely and that was Dystopia: Odyssey. The Odyssey story is a fairly high concept piece of science fiction that tells a story that is integral to the setting as a whole, but which I also layered with a lot of modern socio-political perspective, which is something I try to do with most of the things I write, but don’t always pull off. Odyssey is about sex and misogyny and modern perceptions of masculinity and femininity and how many of those ideas are emphasized by the speed at which they’re realized and enhanced by the massive communication network that they become embodied on. Only later did I realize how true this was going to be when it comes to our own interaction with the World Wide Web. I ain’t no prophet, but it’s been funny for me to see some of this play out the way it has in the last 30 years and to say: “Yeah, that’s kinda what I meant when I wrote…” The ShadowNet is rooted on three of the levels of the city: the third, the fifth, and the seventh. The third and fifth I’ve mentioned already, but the seventh often goes under the radar with most readers, not standing out with features like the Rogue Corps and the Black Market. But the seventh may be the most important of them all, not only for its proximity to the Well, but also because of the regular presence of one of the most central characters in the setting, Hakker. But I’ll get into that some time later.

Anyway, that’s the history of the beginnings of Dystopia as an actual published venture. In the end, the only story that actually had artwork completed and published for it was the Chronicles one (and some pages later completed for Odyssey.) The rest of them remained ether, which is hopefully something we’ll get around to addressing here at some point in the not too distant future.

What some consider to be either the ultimate expression of urban decay in America, an encounter with a cosmic phenomenon, or a nightmare writ large. Regardless, it's somewhere between fascinating and lethal and all shades in between.

- Welcome to Hell, the travelers' guide to Dystopia.

What some consider to be either the ultimate expression of urban decay in America, an encounter with a cosmic phenomenon, or a nightmare writ large. Regardless, it's somewhere between fascinating and lethal and all shades in between.

- Welcome to Hell, the travelers' guide to Dystopia.

3 thoughts on “The grand vision”

Comments are closed.